Reflexive Metrics: Driving stakeholder value and empowering employees through meaningful & evolving measurement

In today’s volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) world, metrics are indispensable tools for guiding decision-making, tracking progress, and fostering improvement. However, the way metrics are developed, implemented, and understood can profoundly influence organizational behaviour and culture. Reflexive Metrics – developed through participative and iterative processes – offer a solution to the pitfalls of traditional output-based measures. They represent an agile, human-centred approach to measurement that emphasizes continuous improvement, employee engagement, and alignment with organizational values.

The Power and Paradox of Metrics

Metrics often aim to provide clarity by quantifying complex concepts like performance or quality. Yet, their simplicity can be misleading. Instead of merely objectively describing reality, metrics shape it.

This shaping power arises because metrics function as quality inscriptions (Dahler-Larsen, 2019). By quantifying complexity, they strip away nuance, rendering phenomena more understandable and comparable. This virtual reduction of complexity helps navigating our ambiguous world by bringing clarity. In this process, we are making a choice what counts as quality – or, in or other words, – what is relevant. This choice facilitates commensuration – the ability to compare, rate, and rank disparate entities based on a seemingly objective standard. For example, a metric like the Net Promotor Score (NPS) reduces the multifaceted experience of customer interactions to a single, interpretable number.

All difference is transformed into quantity”

The benefit of quality inscriptions lies in their utility: they make complex situations actionable. Simplified representations enable organizations to communicate, align on priorities, and make decisions efficiently. Without metrics, the intricate realities of organizational performance could become overwhelming and unmanageable.

However, this simplification comes at a cost. Quality is inherently a social construct, evolving with time and context. Metrics are not static descriptors of an objective reality; they actively define reality in specific ways. For instance, prioritizing a high NPS may shift an organization's focus toward customer-facing improvements, influencing practices and behaviours across teams.

Why Traditional Metrics fall short

Because metrics define what "success" looks like, they have constitutive effects – they shape the behaviours, aspirations, and even identities of those they measure. A sales team evaluated on revenue generation may prioritize short-term gains over long-term customer relationships, while a development team measured on the number of features delivered might sacrifice quality for quantity.

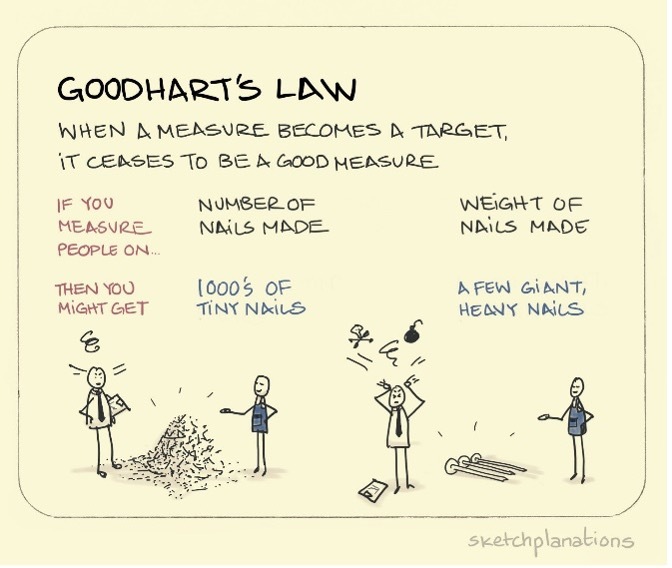

These effects are a double-edged sword. On the one hand, metrics provide a shared understanding of priorities, fostering alignment and driving focus. On the other hand, they risk narrowing organizational effort to the pursuit of metric-driven targets, often at the expense of broader goals. This is where the infamous Goodhart’s Law comes into play:

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure

When metrics shift from being tools for insight to benchmarks for success, or even worse – to control or judge performance – they become susceptible to gaming and lose their effectiveness. As humans, we are incredibly good and innovative at gaming metrics. For example, when employee productivity is measured solely by hours worked, it encourages practices like "mouse-jiggling" to mimic activity rather than focusing on meaningful output. Surely you know a few friends who aced this activity during Covid lockdowns.

Gaming is an example of an unintended consequence of metrics, meaning a constitutive effect that is not wanted. Another likely unintended consequence of using performance metrics is that the focus on meeting quantitative targets can shift employee motivation from intrinsic (aligned with values and goals) to extrinsic (driven by external rewards or penalties) motivation*. The result is often a loss of genuine progress and employee engagement.

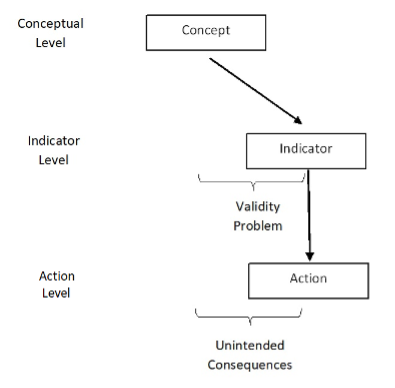

The collection of unintended consequences can be visualised as an evaluation gap: a discrepancy between what metrics measure and what employees, customer or other stakeholders genuinely value. Since metrics are limited in fully capturing the complexity of quality or success, they can inadvertently incentivize behaviors misaligned with organizational goals.

Given the unpredictable nature of our VUCA world, chances are that metrics come with a variety of unintended consequences which cannot be anticipated beforehand. This unpredictability requires a paradigm-shift in how we approach metrics. Instead of oblivion towards the evaluation gap, we require an approach which actively leverages metrics‘ constitutive effects to drive organizational goals forward. This paradigm-shift involves 2 transitions in how we approach and implement metrics:

Paradigm-shift: Transformational Approach to Metrics

First Transition: Moving from Output to Outcome

The challenges inherent in traditional metrics underscore the importance of a shift from output-based to outcome-focused measurement. While outputs emphasize quantifiable activities (e.g., number of tickets closed), outcomes prioritize the value delivered (e.g., customer satisfaction or team growth). Outcome-based metrics align more closely with organizational purpose and employee motivation, fostering a culture of continuous improvement and meaningful work rather than compliance.

Second Transition: Reflexive Metrics

While best practices of both, output- (e.g. Flow Metrics) and outcome based (e.g. OKRs, NPS) metrices, may be useful to gain quick insights and are valuable if used as such, there is no holy grail solution to metrics. This is because of the limited predictability of their constitutive effects and unintended consequences.

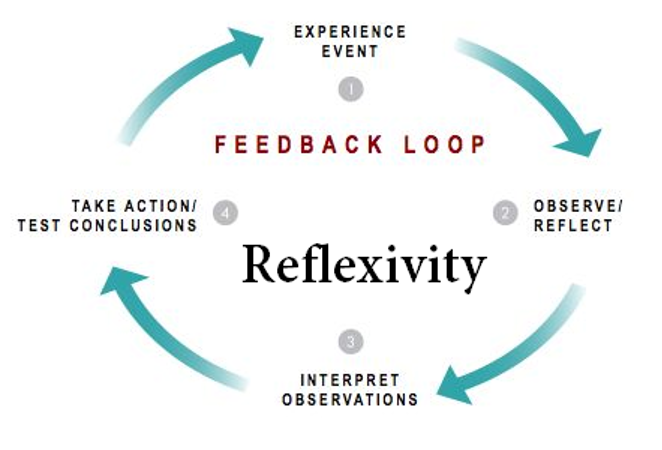

To address the limitations of traditional metrics, organizations must adopt reflexive** and participative approaches. Reflexive Metrics acknowledge the evolving nature of quality as a social construct. They are developed through iterative, participative processes that engage all stakeholders, including employees and customers. This approach does not only align with agile principles, where collaboration and feedback loops are central to success, but also ensures that metrics remain relevant, context-aware, and resilient to unintended consequences.

Key benefits of Reflexive Metrics include:

- Measure what Matters: Bringing enhanced relevance & insight and fostering a customer-centric culture:

By involving those whose work is being measured and how success looks to stakeholders, organizations gain deeper insights into what matters to employees and customers. This participatory approach ensures metrics reflect real-world values, priorities and improvement ideas. Including customer perspectives in metric development reinforces a focus on delivering value, enhancing trust and satisfaction. - Increased Ownership and Engagement

If leadership openly acknowledges that metrics come with an evaluation gap and bring transparency to metric design & implementation, employees gain trust in leadership. Employees participation in metric development furthermore leads to an increased sense of ownership. This fosters intrinsic motivation* and strengthens commitment to achieving meaningful outcomes. - Addressing the Evaluation Gap by Continuous Adaptation

Reflexive Metrics evolve over time to remain aligned with changing organizational contexts and goals. This adaptability helps organizations avoid stagnation and ensures metrics remain effective in gaining insights with respect to value-driven priorities and improvement areas. Given the nature of our complex world, we may never be able to fully close the evaluation gap, but continuous reflection on the effectiveness of implemented metrics can aid the mitigation of unintended consequences such as gaming.

Practical steps for implementing Reflexive Metrics

- Collaborative Development

Engage teams, leaders, and stakeholders in defining what success looks like. Facilitate workshops to explore shared goals and meaningful indicators. - Regular Reflection

Create a culture of continuous deliberation where metrics are regularly reviewed for relevance and unintended consequences. - Balance Quantitative and Qualitative Measures

Complement numerical metrics with qualitative insights to capture the full complexity of organizational performance. - Focus on Outcomes

Shift the emphasis from task completion to the value created for stakeholders.

Conclusion

In a VUCA world, no metric is timeless or immune to manipulation – the holy grail solution to metrics does not exist. Metrics are far more than descriptive tools; they actively shape the realities they measure. By simplifying the complexity of our reality, they aid us to navigate our ambiguous world through bringing clarity on the one hand. On the other hand, this virtual stripping away of complexity also comes with an evaluation gap where the implemented metrics fail to fully reflect on the qualitative concepts they intend to measure.

Reflexive and outcome-based evaluation offers a collaborative & transparent pathway to meaningful measurement by aligning metrics with values, fostering collaboration, and encouraging adaptability. By continuously adapting to evolving contexts, organizations can harness the constructive power of metrics while growing resilient to their unintended consequences. This inherently agile approach not only supports better outcomes for customers but also enhances employee satisfaction & engagement and organizational resilience.

At Gladwell Academy, we specialize in guiding organizations to design and implement effective Reflexive Metrics that drive continuous improvement. Together, we can reimagine how success is measured, creating a work culture that thrives on innovation, engagement, and value creation.

REFERENCES:

Julia’s PhD research:

Heuritsch, Julia (2024), “Reflexive Metrics: Reactivity and Practices of the Evaluation Culture in Astronomy”, https://doi.org/10.18452/28314

Dahler-Larsen, P. (2014), “Constitutive Effects of Performance Indicators: Getting beyond unintended consequences”, Public Management Review, 16:7, p.969-986

Dahler-Larsen, P. (2019), “Quality – From Plato to Performance”, Palgrave Macmillan, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-10392-7

Espeland, W.N. & Stevens, M.L. (2008), “A Sociology of Quantification”, European Journal of Sociology, Volume 49, Issue 03, p. 401 – 436, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003975609000150

FOOTNOTES:

* I actually prefer to talk about autonomous & controlled motivation versus intrinsic & extrinsic, but that may be out of scope here: https://icanbeme.space/index.php/2022/08/30/science-motivation-episode-1/#Definition_Autonomous-Controlled-Motivation

** To read more on the definition of Reflexivity: https://icanbeme.space/index.php/2023/04/06/reflexivity/